This is the third and final part of a blog series by Alan D. D. exploring Edgar Alan Poe and the Gothic. You can read his first post discussing Poe's 'The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar' in relation to death and immortality here, and his second post examining the human mind in 'The Fall of the House of Usher' here.

|

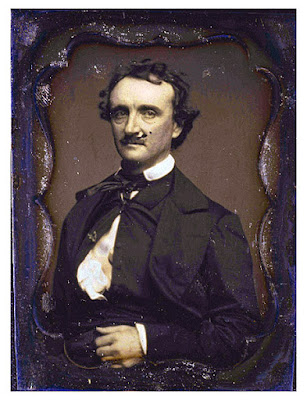

| ('The "Thompson" Daguerreotype' by William A. Pratt) |

Many have written about the effects of art on

humankind. One could not even imagine what life would be with no creative

objects to be appreciated, with no paintings, no music, no drawings, nothing at

all. A person may not have the ability to create, but everyone appreciates a

descent sensitive distraction depending on personal likes. Art is defined by

the Oxford dictionary as ‘the expression or application of human creative skill

and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture,

producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power’

(Oxford Dictionaries, 2018.). It is interesting to note that creativity,

evidently, is linked with the words creator and creation, and one could even go

further and assume it is also a connection to the concept of a Creator, be it a

deity, a mysterious force behind life itself or a scientific event like the Big

Bang, but the association couldn’t be more obvious.

However, it is also reasonable that the power to

create also confirms the power to destroy. Is art, no matter its many forms and

shapes, capable of destroying as much as it is capable of creating? Edgar Allan

Poe seemed to think so, and I am a sceptic to the idea that this was just a

coincidence to find such a proposal in one of his stories.

‘The Oval Portrait’ presents a rather unsetting plot:

an anonymous traveler, who is also injured, finds refuge in an abandoned

mansion in the Apennines, and in the night discovers a painting with a

disturbing story, that of an artist that turned the soul of his wife, which was

also the model, into a piece of art and so killing her: ‘the painter (who had

high renown) took a fervid and burning pleasure in his task, and wrought day

and night to depict her who so loved him, yet who grew daily more dispirited and

weak.’ (Poe, 1845). The first thing I can think about is that this is clearly

some form of obsession-leaded vampirism. It is not enough for this artist, this

husband, to slowly steal his wife’s life in an attempt to immortalize her, so

he needs and has to complete the painting, not even aware that he would widow

right away, making an artist, which also means a creator, a destroyer of life

as well (Meyers, 2000.).

|

| ('The Oval Portrait' by Jean Paul Laurens) |

Vampires have also been linked with obsession by

different psychological conditions. Medicine has a term for this mania to drink

blood: Renfield Syndrome. This syndrome is named after a character in Bram

Stoker’s Dracula, and it is interesting to note that individuals who are

part of vampire cults ‘may also demonstrate certain psychopathologies such as

dissociation, obsessive thought, delusional thinking, and hallucinations’

(White & Omar, 2010: p. 192.). This becomes relevant when we discover that

Poe’s first version of this tale, titled ‘Life in Death,’ published in Graham's

Magazine in 1842, included details on how the narrator had been wounded and

that opium was used to relieve the pain. However, the author eliminated this

part of the narration for considering it made the story be seen as a

hallucination (Sova, 2001.).

It doesn’t matter if the narrator is living this or

only imagining it. Either way, it is clear that this characters has some kind

of mental imbalance just like the artist, for it is stated that the narrator ‘thinking

earnestly upon these points, I remained, for an hour perhaps, half sitting, half

reclining, with my vision riveted upon the portrait’ and more explicitly that ‘in

these paintings my incipient delirium, perhaps, had caused me to take deep

interest’ (Poe, 1845.).Yet, I’m inclined to think that maybe there was

something worse, something Poe tried to avoid and process, when he wrote this

tale, if we consider that ‘horror stories are a means through which artists

implicitly comment on the state of human affairs at a particular moment’

(George & Green, 2015: p. 2345.).

It was around this time, when ‘The Oval Portrait’ was

written, that Poe’s wife, Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe, started a health decline

that would end on her dead in 1847, (Silverman, 1991,) and which the writer

himself stated made him ‘insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity’ (Poe,

1848.). This could suggest that Poe had an ambiguous, bittersweet relationship

with his work: although it offered him a distraction from reality, an escape

from the inevitable event that would cause him a severe depression, maybe he

felt his art was somehow murdering his own wife. He didn’t need to be part of a

vampire cult, for in his mind he was a vampire already.

These creatures have been linked with sexuality,

sexual desire and liberation (Hughes, 2012,) but

it is clear that obsession, death and life also play an important role on the

figure of the vampire, which, apparently, is also capable of becoming an

artist, ‘the creator of beautiful things,’ (Wilde, 2014,) given the impact and

influence this tale had. Some may be familiar with a certain Mr. Gray, which story

was inspired by this tale of Poe, and whose writer praised Poe’s work five

years before Gray was born (Sova, 2001.).

References

Sova, D. B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe A to Z:

The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts on File.

Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore - Works - Letters

- E. A. Poe to G. W. Eveleth (January 4, 1848). (2018). Retrieved from https://www.eapoe.org/works/letters/p4801040.htm

George, D. R., & Green, M. J. (2015). Lessons Learned From Comics Produced by Medical Students: Art of Darkness. Jama, 314 (22), 2345-2346.

Hughes, W. (2012). Fictional Vampires in the

Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. In D. Punter, A New Companion to

The Gothic (pp. 197-210). New York, NY: John

Wiley & Sons.

Meyers, J. (2000). Edgar Allan Poe: His Life

and Legacy. New York: Cooper Square Press.

Oxford Dictionaries. (2018). Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/art

Poe, E. A. (1845). The Oval Portrait. Alex Catalogue.

Silverman, K. (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: Harper

Perennial.

White, M., & Omar, H. A. (2010). Vampirism,

vampire cults and the teenager of today. International

journal of adolescent medicine and health, 22(2), 189.

Wilde, O. (2014). The

Picture of Dorian Gray. Urbana, Illinois: Project Gutenberg. Retrieved June

13, 2018 from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/174/174-h/174-h.htm

Alan D. D. is an author, blogger and journalist who has been freaking the world since 1995. Hailing and writing out of Venezuela, Alan D.D. has worked with books, comics, music, movies and almost anything else that catches his attention. 99% of the time, it's something about witches. He's currently trying to get his first novel in English published and searching for a 24/7 chocolate supplier.