His peculiarities caused him to be invited to every house; all wished to see him, and those who had been accustomed to violent excitement, and now felt the weight of ennui, were pleased at having something in their presence capable of engaging their attention. In spite of the deadly hue of his face, which never gained a warmer tint, either from the blush of modesty, or from the strong emotion of passion, though its form and outline were beautiful, many of the female hunters after notoriety attempted to win his attentions, and gain, at least, some marks of what they might term affection.

John William Polidori, TheVampyre; A Tale (1819)[i]

This blog was originally posted on the 'Romantic Legacies' blog.

The charming elegance of the aristocratic vampire, fully formed in Bram Stoker’s seminal Dracula (1897), was certainly born out of a centuries-long preoccupation with vampirism and vampire imagery that adorned politics, society, and literature. Although it may seem like a Victorian literary trademark (Dracula is exclusively responsible for this), the vampire actually flourished in England from the eighteenth century onwards. In a fairly extensive manner, literary criticism has drawn attention to Polidori’s Byronic The Vampyre 1819), and the enthralling Lord Ruthven is evidently a mishmash product of the gloomy atmosphere of the ghost story competition that took place in Byron’s villa in the summer of 1816, and Polidori’s idiosyncratic relationship with Lord Byron, of which Lord Ruthven is a lurid reference.[ii] Despite setting the ground for the vampire-as-aristocrat trope, however, Polidori’s creation was not candidly original. Already, Lord Byron’s powerful reference to the vampire in his Oriental The Giaour (1813) betrays some of the cultural characteristics of vampiric figures in the nineteenth century:

But first, on earth as Vampire sent,

Thy corseshall from its tomb be rent:

Then ghastly haunt thy native place,

And suck the blood of all thy race. (ll. 755-8)[iii]

Clearly, Byron’s vampire betrays echoes of hauntedness, corpse reanimation, and familial blood-sucking, which were all more or less considered hallmarks of vampirism. In a note to The Giaour, Byron further testifies to his perennial knowledge of the vampire legend:

The freshness of the face, and the wetness of the lip with blood, are the never-failing signs of a Vampire. The stories told in Hungary and Greece of these foul feeders are singular, and some of them most incredibly attested.[iv]

In placing the origins of the vampire in Hungary and Greece, Byron restates the vampire’s orientalism, and contextualises its contemporary resurrection in these countries’ oral traditions, much in a similar way as Robert Southey’s Thalaba the Destroyer (1801) did before him.

From the moment of the first vampire appearance in literature, works like Gottfried August Bűrger’s ‘Lenore’ (1774) infiltrated the English imagination by adding to the orientalised tradition of the seductive, bloodthirsty vampire.[v]Even before ‘Lenore’, Alexander Pope’s 1740 letter to Dr. William Oliver imports an unexpected reference to the German (literary) origin of the Vampire, coupled with folkloric knowledge of the vampire’s practices and extermination by way of driving a stake through the vampire’s heart.[vi]Especially after the Augustans, by the end of the eighteenth century there is a marked rise of sensationalist Gothic literature that helped shape Gothic Romantic works. This shift to the macabre was not asymptomatic of a gradual but steady turn to individualised experience and psychology. Who is better to symbolise the grimness of reality and the human unconscious, than a creature that embodies fears and anxieties by defying all laws and boundaries?

The history and transformation of the vampire figure throughout the centuries is a colossal topic that I am not attempting to unravel here. Suffice to say that, by the time the vampire reached England, the creature seemed to be a ‘mixture of Slavic, Scandinavian, and Greek stock’,[vii] soon to evolve into an alluring character that was almost exclusively demonised and, more often than not, deeply politicised. The influence was shift; translations and literary variations started to proliferate.

Following this, Samuel Taylor Coleridge was among the first to refer to vampirism in his The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), published in the first edition of Lyrical Ballads(1798). There, in the vast expanse of the deadening sea, the Mariner describes their unremitting thirst:

With throats unslaked, with black lips baked,

We could nor laugh nor wail;

Through utter drought all dumb we stood !

I bit my arm, I sucked the blood,

And cried, A sail! a sail![viii] (ll. 149-53)

This image of blood sucking appears the moment of a ghastly ship looms in the horizon, and the whole atmosphere tantalises by marking the Mariner’s gradual preparation to meet the vampiric Nightmare Life-in-Death, another meticulous reference to the vampire’s undead state, red lips, and white skin (ll. 191-3). As an embodiment of fear, Life-in-Death seems to drain the Mariner’s blood: ‘Fear at my heart, as at a cup, /My life-blood seemed to sip (ll. 200-1). Life-in-Death and her mate, Death, are interchangeable in their play on human fear.

|

| (William Strang, Death and Life-in-Death, plate 8 from The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, 1896) |

Coleridge’s Geraldine in his Gothic ballad Christabel (1816)[ix]is the female seducer kind of vampire. From the beginning, she is described as romantically otherworldly, ‘Like a lady of a far countree’ with eyes that ‘glitter bright’, in such lovely voluptuousness that the narrator urges to ‘shield her! Shield sweet Christabel!’ (p. 8). It is even more suggestive that Geraldine appears in Christabel’s dream as ‘a bright green snake / Coiled around its [the dove’s] wings and neck, / And with the dove it heaves and stirs, / Swelling its neck as she swelled hers’ (p. 19). The mastiff’s ‘angry moan’ when it sees Geraldine (p. 6), Geraldine’s snaky eyes (p. 20), and the fact that Geraldine seems not able to pass through water, are implicit signs of Geraldine’s vampiric qualities and demonisation. Coleridge’s Geraldine is certainly one of the most distinct depictions of the eroticised female vampire, as in J. Sheridan LeFanu’s Carmilla (1872), which seems deeply influenced by Coleridge’s Christabel. As in the latter, Carmilla features a temptress female vampire that combines the Byronic vampire’s aristocratic lineage and Geraldine’s seductiveness. The plotline is also similar, but LeFanu’s novel moves more conspicuously along the grotesquery of the German School of Horror, of which ‘Monk’ Lewis is a famous example. As Richard Norton claims, German horror tales ‘were very influential on English works, and some of the Gothic novelists, especially Matthew Gregory Lewis, were well versed in German folk tales and ballads of the supernatural’: more precisely, these ‘Sensationalistic ‘raw head and bloody bones’ are more characteristic of the School of Horrorand partly help to define it. Full-bodied demons have replaced the filmy spectres of the School of Terror’.[x] In contrast to Christabel, Carmilla’s open description of gloated vampirism is finalised by an even more informed but rough-hewn description of exorcising Countess Mircala’s demonic influence:

Here then, were all the admitted signs and proofs of vampirism. The body, therefore, in accordance with the ancient practice, was raised, and a sharp stake driven through the heart of the vampire, who uttered a piercing shriek at the moment, in all respects such as might escape from a living person in the last agony. Then the head was struck off, and a torrent of blood flowed from the severed neck. The body and head was next placed on a pile of wood, and reduced to ashes, which were thrown upon the river and borne away, and that territory has never since been plagued by the visits of a vampire.[xi]

We clearly see LeFanu’s reiteration of yearlong folkloric traditions connected to the interment, staking, and decapitation of vampires, described in this passage with the coolness and precision of contemporary scientific and legal nineteenth-century treatises and records on vampirism and animality.

|

| (From The Dark Blue by D. H. Friston, 1872) |

As in Christabel, we find in Carmilla this association of vampirism with animality; Laura’s account of ‘a sooty-black animal that resembled a monstrous cat’ is pertinent to the way the vampire bordered on the animal, and worse, because of its ghastly shapeshifting and its status as macabre predator:

It appeared to me about four or five feet long for it measured fully the length of the hearthrug as it passed over it; and it continued to-ing and fro-ing with the lithe, sinister restlessness of a beast in a cage. I could not cry out, although as you may suppose, I was terrified. Its pace was growing faster, and the room rapidly darker and darker, and at length so dark that I could no longer see anything of it but its eyes. I felt it spring lightly on the bed. The two broad eyes approached my face, and suddenly I felt a stinging pain as if two large needles darted, an inch or two apart, deep into my breast. I waked with a scream.[xii]

This affinity between vampirism and animality is also evident in verbal and pictorial depictions of vampirism and vampire bats in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which could also acquire socio-political dimensions. For example, accounts on British periodicals in 1819 describe the Vampire bat as

(…) in general about a foot long, and the spreading of its wings nearly four feet; but it is sometimes found much larger, and some specimens have been seen of six feet in extent. Its general colour is a deep reddish brown. The head is shaped like that of a fox; the nose is sharp and black; and the tongue pointed.[xiii]

The almost supernatural way in which the body of the vampire bat is depicted is also evident in Groom’s record, who also points to the way such ‘creatures’ were reported to ‘come at night’, ‘suck blood’, and even kill.[xiv]William Blake was extremely interested in vegetable, zoology, and insect studies, and his representation of Los’s Spectre in Plate 6 of his Jerusalem (1804-8) bears something of the vampire bat description, especially in its physiology/stature.

|

| (William Blake, Jerusalem, Plate 6) |

Another example of illustrated vampirism in Blake’s portfolio is his The Ghost of a Flea (1819-20), both tempera and paper, which represents an anthropomorphic flea that is drawn invariably with fangs and a cup of blood on its hand. Considering Blake’s position as a visionary poet that responded to a personal calling, The Ghost of a Flea can be seen as something more than Blake’s illustration for John Varley’s Treatise on Zodiacal Physiognomy (1828). The choice of a flea as a symbol of parasitism is especially political when it comes to Blake’s representations of the fallen world, and the fallen body.

|

| (William Blake’s The Ghost of a Flea) |

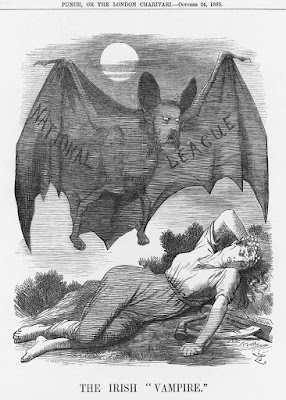

Political vampirism answered contemporary needs to talk about a diseased body politic drained by external threat, whether in Britain or abroad. The vampire turned into a symbol way into the nineteenth century, appropriated and utilised for political commentary. In his 1882 political cartoon, for instance, George Frederick Keller finely illustrates blood-sucking landlords as vampires who feed off their tenants and then burn in hell for their sins.

|

| (Thomas Nast, Political Vampire, Harper’s Weekly (1885)) |

|

| (The Irish Vampire, London, 1885) |

|

| (George Frederick Keller, The Vampires, Or the Landlords of San Francisco, 1882.) |

What all these political illustrations have in common with literary vampirism is a sharp attention to the animalistic qualities of the vampire, and the vampire’s profound crossbreeding. We have already encountered Geraldine’s portrayal as a snake, and Carmilla’s transformations into a black cat. Similarly, we find in John Keats’s Lamia (1820) a description of Lamia’s body that very much resembles that of a fantastic snake-beast:

She was a gordian shape of dazzling hue,

Vermilion-spotted, golden, green, and blue;

Striped like a zebra, freckled like a pard,

Eyed like a peacock, and all crimson barr’d.(ll. 47-50)[xv]

Her enthralment of the Corinthian youth named Lycius places her in the literary tradition of the demonic seductress who entices the unsuspected youth to ‘unperplex’d delight and pleasure’ (ll. 327), at least until she is melted by Apollonius’s gaze:

Do not all charms fly

At the mere touch of cold philosophy?

There was an awful rainbow once in heaven:

We know her woof, her texture; she is given

In the dull catalogue of common things.

Philosophy will clip an Angel's wings,

Conquer all mysteries by rule and line,

Empty the haunted air, and gnomèd mine—

Unweave a rainbow, as it erewhile made

The tender-person'dLamia melt into a shade. (ll. 229-38)

As creatures that defy reason, then, vampires cannot stand rational scrutiny, and dissolve before any scientific explanation of them finds solid ground. As Groom says, vampires signified a ‘black illumination to the Enlightenment, by challenging the epistemological foundations of rationalism and empirical knowledge’.[xvi]And whether or not explicitly vampiric, demon creatures like the vampire suffuse Romantic literature and foreground the reader’s greatest fears, inviting the reader to participate in the complex interplay between victim and predator. In doing that, we are in a similar position to Keats’s knight at arms in his La Belle Dame Sans Merci (1819), who sees ‘pale kings and princes’ (ll. 37) with ‘starved lips’ (ll. 41)[xvii] in his dream, forewarning him of the dangerous belle that lures him.

To go back to male vampires in Romantic literature, it was certainly ‘a most attractive demon’ especially ‘to the second generation of Romantics’; although not conventionally vampiric, the Byronic Hero ‘already had many of the mythic qualities of the vampire: here was the melancholy libertine in the open shirt, the nocturnal lover and destroyer, the maudlin, self-pitying, and moody titan, only a few years away from Nietzsche’s Superman.[xviii] Byron himself was to provide a most vivid inspiration for Polidori’s 1819 novel. However, even before this time, the fascination of German vampires quite captivated poets like Coleridge who gradually move away from literal depictions of vampires to a more psychologised symbolism of the vampire figure and the qualities of vampirism.[xix]Real or symbolic, however, vampires made their way into Romantic literature in the context of emergent Gothic Romanticisms that shared in vampire discourses of the time, and were ready to re-invent vampirism in new and political ways.

Elli Karampela is a PhD Researcher at the School of English of the University of Sheffield. She is mainly interested in English Romanticism, and all things dark in relation to English Romanticism. She is an assiduous reader of (particularly Gothic) eighteenth and nineteenth-century texts, and a proud member of Sheffield Gothic. She is also a representative of the Messolonghi Byron Society, as well as the Centre for Nineteenth-Century Studies at the University of Sheffield, and an organiser of the 'Culture Vultures' reading group.

[i]Polidori, John William. The Vampyre; A Tale (London: Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, 1819), p. 28.

[ii] Groom, Nick, The Vampire: A New History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), p. 109.

[iii]George, Gordon, Lord Byron, TheGiaour, A Fragment of a Turkish Tale (London: John Murray, 1814), p. 37.

[iv] George, Gordon, Lord Byron, TheGiaour, A Fragment of a Turkish Tale (London: John Murray, 1814), n. 38, p. 38.

[v] Groom, p. 99.

[vi]Twitchell, James, The Living Dead: A Study of the Vampire in Romantic Literature (USA: Duke University Press, 1981), p. 8.

[vii]Ibid., p. 7.

[viii] Coleridge, Samuel Taylor, ‘The Rime of the AncyentMarinere’ in Lyrical Ballads, by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, (London: Routledge, 2005), pp. 51-78 (p. 58).

[ix] Coleridge, Samuel Taylor, Christabel and the Lyrical and Imaginative Poems of S.T. Coleridge, ed. by Algernon Charles Swinburne (London: Sampson Low, Son, and Marston, 1869)

[x]Norton, Rictor, Gothic Readings: The First Wave, 1764-1840 (London: Leicester University Press, 2000), p. 106.

[xi] LeFanu, Sheridan J., Carmilla (Doylestown: Wildside Press), pp. 142-3.

[xii] LeFanu, Carmilla, p. 69.

[xiii] ‘Natural History of the Vampyre Bat’, in Fictitious History of the Vampyre, The Imperial Magazine (British Periodicals, 1819), pp. 235-240 (p. 240). In the same entry, letting aside that the Vampyre bat is, according to the writer, vegetarian, the association of the bat with the figure of the vampire, a creature that devours the victim with such voracity ‘as to cause the blood to flow from all the passages of their bodies, and even from the very pores of their skin’, marks the creature as bordering on monstrosity (p. 237).

[xiv] Groom, p. 112.

[xv]Keats, John, ‘Lamia’, in Poetical Works (London: Macmillan, 1884; Bartleby.com, 1999) www.bartleby.com/126/.

[xvi] Groom, p. 93.

[xvii]Keats, John, ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’, in Poetical Works (London: Macmillan, 1884; Bartleby.com, 1999) www.bartleby.com/126/.

[xviii]Twitchell, p. 75.

[xix]Ibid., p. 156.